Frederick Simon Fiedler (1835-1901)

Frederick Simon FIEDLER was born on the 8 June 1835, in the small town of Eckartsberga, in the province of Saxony, in what is modern-day central Germany. During Frederick ’s childhood this was part of the Kingdom of Prussia. He was the youngest son of Johann Christian and Emilie FIEDLER. In Christmas of 1852, when Frederick was 18, his mother died.

In September of 1854, Frederick, just 19 years old, made his way to Bremen to sail to America. Frederick obtained passage on the New Era, a clipper chip newly built in Maine that had just launched in April of that year. His steerage ticket likely cost $16, perhaps more; after inflation that ticket would cost $600 today. This was the ship’s first trip across the ocean, homeward bound. There were 426 souls on board – 5 first class passengers, 6 second cabin passengers, 374 steerage (of which Frederick would have been counted), 29 crew and 12 passenger cooks. There was also a significant cargo aboard as well.[1]

Travel on board these boats as an immigrant was uncomfortable at best. There were few laws governing safety (at the time, more humane laws governed the slave ships from Africa than the emigration ships from Europe). The overwhelming number of people seeking refuge in America strained the ports of Europe, and Bremen was one of the most popular ports from which to depart. Bremen was one of the most popular ports for emigration, especially during the latter part of the 1800s. It is estimated that over 7 million people have emigrated from Bremen over the last two centuries.

Ship fires were common, as were collisions and accidents, and conditions were miserable, especially for those traveling in steerage. Leaving the fresh air and sunlight on the upper deck passengers had to descended a steep ladder. Trunks and baggage filled the center hold, and the passenger compartments were windowless, and not big enough to sit upright. The crowded ships meant steerage passengers slept four to a bunk, and sometimes in the gangways. Toilets consisted of buckets behind screens.[2]

The New Era experienced difficulties from the beginning. It was delayed departing from Bremen for 10 days and eventually set sail for New York on September 28, 1854. Cholera broke out on the ship, killing one before they departed Bremen. Over the course of the journey, the cholera outbreak would kill more than 30 passengers. Passenger Louisa Haeier later provided a statement on the journey and she gave the number at 42. Louisa said: “I cannot give a name to the disease of which they were the victims; I only know that, generally, they sicked at nightfall and were cold before morning … those unfortunates had been exhausted by want of proper food and fresh water – many of them having been reduced to drink of the water of the sea.”[3]

The rations during the trip were subpar at best. At the time, a child under 8 would have been counted as half rations, and an infant not counted at all. While the captain later stated that he stocked the ship according to standard procedure, the passengers would report a lack of quality food, that they would have to hire cooks from among themselves as the food was inadequately prepared. Even the captain admitted to a problem with the first mate that was never addressed in the aftermath of what was to come. The ship’s doctor was also notably brutal. “The conduct of the doctor towards those sick persons under his charge was characterized by extreme brutality;” Louisa Haeier stated, “It was, in fact, a voyage full of the misery of sickness and want, and, at a later period, of danger and death.”[4]

The ship faced strong winds throughout the passage. On October 20 the ship was struck by waves so strong the cooking range used for the passengers in steerage came loose and crushed several passengers to death, injuring some crew as well. The turbulent sea and the large waves caused leaks in the boat, and the pumps were employed to keep the New Era from sinking. For four days the steerage passengers worked in gangs on the pumps trying to keep her afloat. On the evening of Sunday, November 12, the weather was stormy, and the seas were rough. The captain had lost track of their location, assuming them to be off the coast of Long Island, when in fact they were further south, along the northern coast of New Jersey. At approximately 6:00 a.m. on Monday, November 13, the ship struck an outer sand bar about 400 yards off Deal Beach.[5]

When the ship struck the passengers were alerted by the crew members to come on deck to be saved, but passenger Louisa Haeier noted that many did not speak English and were confused as to what was happening. Those that understood frantically tried to dress and grab anything of worth they had brought with them to America – gold, money, jewels – as they scrambled to the deck. Unfortunately, many were washed overboard, or crushed, when the boat struck the ocean floor, and the waves began to pummel the boat. After the shipwreck it was reported that the ship doctor had stolen jewels and money from passengers before making his attempted escape and drowning.

One of the passengers, Gaspar or Cooper Baberich, is listed in close proximity to Frederick FIEDLER on both the passenger manifest and the lists of survivors afterwards. He later gave a detailed description of how he was able to survive the wreck. We can assume that his words are as close to a firsthand description as we might have gotten from Frederick himself.

Baberich describes: “water rushing into the hold in a perfect torrent, and the breaking of the spray over the deck as she swayed to and fro in the heavy sea. The deck commenced breaking up rapidly, and portions of the cargo were forced up from the hold, tearing up the planks. Several of the passengers were crushed to death between barrels, casks and boxes, and were afterwards swept overboard by the waves in a horribly mutilated condition…. A terrible scene of excitement ensued on board among the passengers, some of whom clung to the sailors with a terrible tenacity, imploring them to save them. The sailors…got out the boats, determined to save their own lives. The passengers made a rush for the first boat when it was lowered, but the sailors stood before it with drawn knives and threatened to kill any who attempted to get into it.

Finding it impossible for myself or any of the others to make our escape from the vessel…I determined to taking to the rigging as a last resource. I clambered as well as I could up the foremast, and succeeded with nine others, four of whom were sailors, in getting into the cross trees. This was about 12 o’clock in the day, after four days of most exhausting labor in trying to keep the ship free from water.”[6]

As the light came up that morning, and the fog lifted, townspeople watched from the beach as the huge waves lifted the ship off the outer bar and tossed her about 150 yards from the beach, leaving her broadside to the shore and vulnerable to the waves now crashing over the decks. She sank in less than an hour. Remaining the New Era’s rigging clung nearly 400 souls, holding on for dear life in the freezing cold, buffeted by wind and water.”[7] Frederick FIEDLER was lucky enough to have found a spot in the rigging and he clung to it through the long night and into the next day.

As darkness fell, the rescuers could no longer reach the ship and lit bonfires on the beach for encouragement while FIEDLER and his fellow passengers clung to the rigging in the cold and under assault from the sea. “Here we remained till six o’clock the following morning, when we were taken off by surfboats. We saw several of our unfortunate fellow passengers swept off other parts of the rigging without being able to render them any assistance; and I shall never forget the fearful scream of agony that burst from them as they were engulphed in the waves.”[8]

Capt. Smith of the News Yacht of the Associated Press, from on board the Steamboat Achilles, which was sent to assist, reported on the stunning lack of rescue boats available, even though at 4:30 in the afternoon the waves had subsided enough that he thought a rescue operation could have been launched. There was miscommunication between steamboats that were equipped to provide aid. While the men on shore and the captains of the steamboats tried to ascertain the best solution forward, FIEDLER and the other survivors clung to life on the masts.

“We were near enough to distinctly see women holding their little ones with one hand,” wrote Capt. Smith, “while the other, bleached by the spray, clung with a death grip to the ratlines on which they stood. On one or two in the mizzen rigging having on but a shirt. On the forecastle there stood a few moments ago, a group of four clinging to the sway, but they are now gone – a heavy swell has probably swept them away. Men have been seen to fall from the jibboom into the surf.”[9]

After over 24 hours they were finally reached by surfboat and rescued. Exhausted, battered, and stripped of all goods (and in many cases clothing), upon reaching the shore some perished from their trauma. The dead would continue to wash ashore for up to a year. Overall, the death count was as high as 280; around 140 were buried in a mass grave at the Old First United Methodist Church in West Long Branch, New Jersey.[10]

After the wreck, Frederick boarded a passing steamship bound for New York City, along with many of his fellow surviving steerage passengers. At that time, Manhattan had the largest German population of any city in the world outside of Berlin and Vienna.[11] Much of the Lower East Side of Manhattan in 1855 was referred to as Kleindeutschland (Little Germany). When the survivors arrived, they were cared for by the German Society of New York, who appealed to local citizens for donations of clothing and other funds.[12] The society was able to raise enough for $40 and a suit for each of the near 140 survivors.[13]

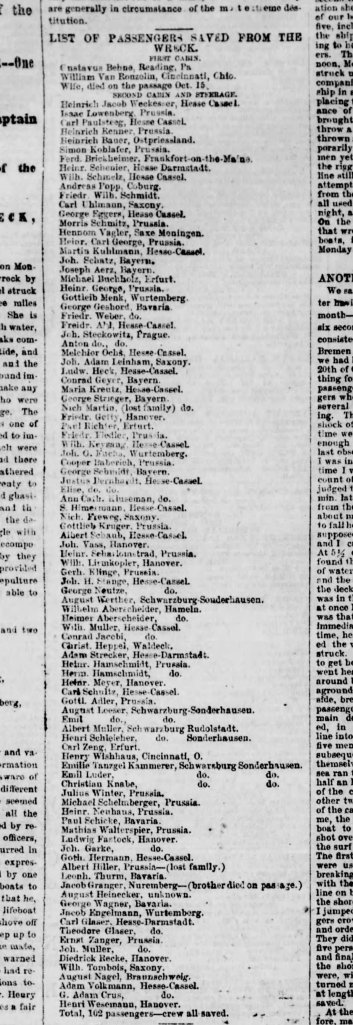

“Friedr. Fiedler” in the list of passengers saved from the wreck.

The loss of the ship New Era led directly to the creation of the United States Lifesaving Service, which would eventually become the U.S. Coast Guard. The tremendous loss of life, the horrific details of the shipwreck, and the inability of officials to provide lifesaving care became the lynchpin which would stimulate the development of ocean rescue operations as we know them.

Frederick FIEDLER would take his $40 and his new clothes from the German Society of New York City in 1854 and make his way north. Sometime in late 1857 he married Theresa HARTWICK in Norwalk, Connecticut.

Theresa HARTWICK was also a German immigrant. She was born in Saxony in March of 1837, the eldest daughter of John and Barbara (SCHERPFIN) HARTWICK. In June of 1854, the family immigrated to the United States, arriving in New York City from Bremen on the ship Wilhelmine. The family settled in Norwalk where John, a skilled tradesman (a joiner) in Prussia, worked as a saloon keeper while Barbara tended house. Teresa had one sister, Franciska (“Frances” b. 1840) and three younger brothers, Joseph (b. 1844), Antony (b. 1846) and John Baptist (b. 1850).

The “Hartwig” family listed on the passenger manifest for the brig Whilhelmine, arriving in New York, June 1854 from Bremen

In 1860 U.S. census the FIEDLER family was living in Westport, Connecticut. Frederick worked as a day laborer and the young couple had two daughters – Frances (b. 1858) and Theresa (b. 1859).[14] In 1866 they welcomed a son, Frederick Simon Jr., and in 1867, another son, Joseph. By 1870, Frederick senior had become a naturalized citizen and was working as a fireman. The same year, a son was born named John. Their last child, daughter Mary Emma, would follow in 1873.

In 1880 the family was settled in Norwalk and Frederick and his eldest daughters were employed at the local woolen mill. Frances (called Fanny) suffered from liver disease. Young son Joseph, now 13, was kept home from school with “chills.” Joseph would never quite recover from his illness and died in 1886 at age 19. Fanny seemingly did recover from her liver disease enough to live a full life. She married in 1881 and eventually had five children. Young Theresa also married in 1881 and would have three young children of her own, although sadly one would die in infancy.

In 1887, his namesake son Frederick Jr., married Edith Mae WEED, a young girl from a distinguished Norwalk lineage. They had two daughters: Florence (Flossie b. 1889) and Leola (b. 1895). Sometime before 1900 Edith lost a baby in childbirth. In 1905 Frederick Jr. and Edith FIEDLER would welcome a son who they named Harry Frederick.

Frederick FIEDLER continued working in the local mills for the duration of his life. He died in Norwalk in May of 1901 at age 65 and was buried in the Norwalk Union Cemetery alongside his young son, Joseph. Theresa (HARTWICK) FIEDLER lived another 22 years – living at varying times with her son John and his wife, and with her daughter Mary Emma’s family. Theresa FIEDLER died in January 1923 and was buried beside her husband and son.

The story of Frederick’s survival on the New Era did not pass down through the generations. It was not a legend of heroics told at bedtime. There were no news clippings, no visits to the Jersey shore to reminisce. Frederick seems to have taken the trauma to his grave – we cannot know if even his children knew what he suffered to bring their future to the shores of the United States.

German immigrants flourished in New York City up until the early part of the 20th Century, when several events would bring about the end of Little Germany. The sinking of the steam-paddle boat, the General Slocum, which was chartered to take over 1,300 women and children from St. Mark’s Evangelical Lutheran Church to Long Island for a summer picnic, ended in disaster – the boat caught fire and killed all but 400 passengers. Over 600 German families in New York City lost family in the tragedy – the largest loss of life in a ship accident until the Titanic, and the largest loss of life in NYC until September 11, 2001.[15] In addition, anti-German sentiments prevailed leading into the first World War. German immigrants began to leave the city and find their way to outer boroughs and other states. However, much of the architecture and the history established in the 1800s remains today.

[1] “Statement of Thomas J. Henry, The Commander of the New Era to the Editor,” New York Daily Herald, Thu Nov 16 1854, page 8.

[2] https://www.revisionist.net/hysteria/german-exodus.html

[3] “Statement of Louisa Haeier, Passenger [translated],” New York Daily Herald, Thu Nov 16 1854, page 8.

[4] Ibid.

[5] “Another Statement by Captain Henry,” New York Daily Herald, Thu Nov 16 1854, page 8.

[6] “Statement of Gaspar Baberich, of Ham, Prussia,” New York Daily Herald, Thu Nov 16 1854, page 8.

[7] https://jerseyshorescene.com/shipwreck-the-death-of-the-new-era/

[8] Ibid

[9] “Wreck of the Ship New Era, Letter from Capt. Smith of the News Yacht of Associated Press,” The Charleston Daily Courier, Fri, Nov 17, 1854, Page 1.

[10] https://jerseyshorescene.com/shipwreck-the-death-of-the-new-era/#:~:text=The%20following%20day%2C%20a%20boat%20was%20launched,of%20the%20dead%20disappeared%20into%20the%20sea.

[11] https://lespi-nyc.org/kleindeutschland-little-germany-in-the-lower-east-side/

[12] New York Daily Herald, New York, New York, Sat, Nov 18, 1854, Page 5

[13] Brooklyn Eagle, Brooklyn, New York, Tue, Nov 28, 1854, Page 2

[14] U.S. Federal Census 1860: Westport, Fairfield, Connecticut; Roll: M653_75; Page: 104; Dwelling 830/Family 858

[15] https://www.nyhistory.org/blogs/witness-to-tragedy-the-sinking-of-the-general-slocum