Arnold LaPorte (1803-1885)

Arnold LAPORTE was born in Lippstadt, Prussia, in August of 1803. He was baptized Conrad Arnold on 17 September 1803 at Great Marienkirche (St. Mary’s Church) in Lippstadt, Westfalen, Prussia – son of Johann Phillip and Caroline Catharine (WINCKEL) LAPORT. Westfalen, or Westphalia in modern Germany, was a province of the Prussian empire that sits in the North West near Dusseldorf, close to the border of the Netherlands to the North and Belgium to the West. This area of Prussia was once a Polish fiefdom, and then part of Lower Saxony as the Lower Rhine-Westphalian Imperial District. Around the time of Arnold’s birth, and early childhood, Lippstadt was incorporated into the French Empire under Napolean.[1] The Napoleanic Wars would have spent much of his early youth, after which the Kingdom of Prussia was established in 1816. [2]

In April 1831, Arnold married Friedericke Elise SCHABBEHARD in Lippstadt, in the same church where he was baptized. There they baptized a son, Johann Heinrich, on June 24 of the same year.

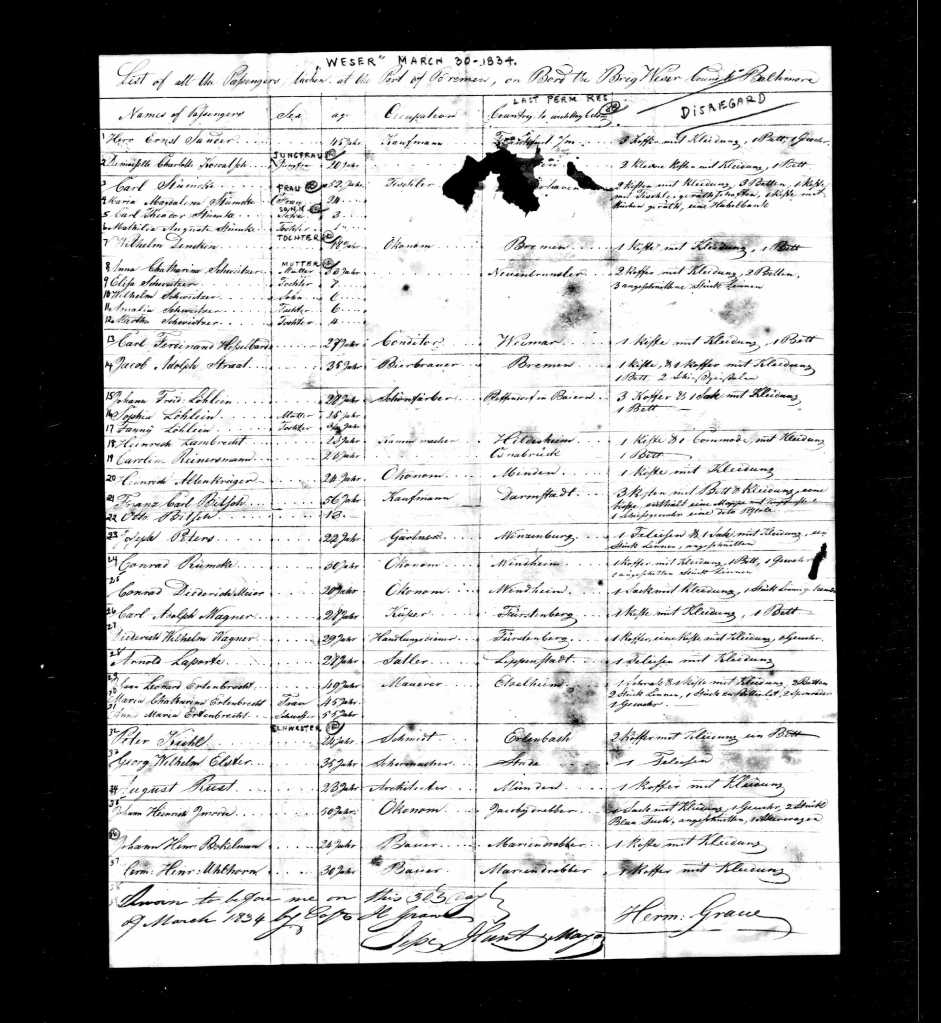

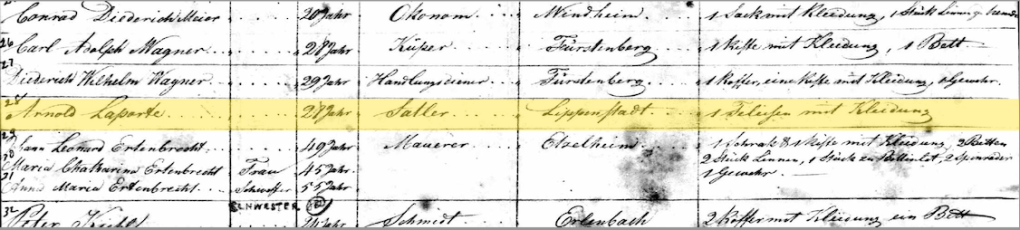

In 1834, Arnold immigrated to America alone with only “one valise with clothing” to begin a new life. Arnold came to Baltimore on the ship Weser, departing from Bremen, and arriving on March 30, 1834.[3] His wife and child remained behind in Prussia. No death or immigration records for either have been found.

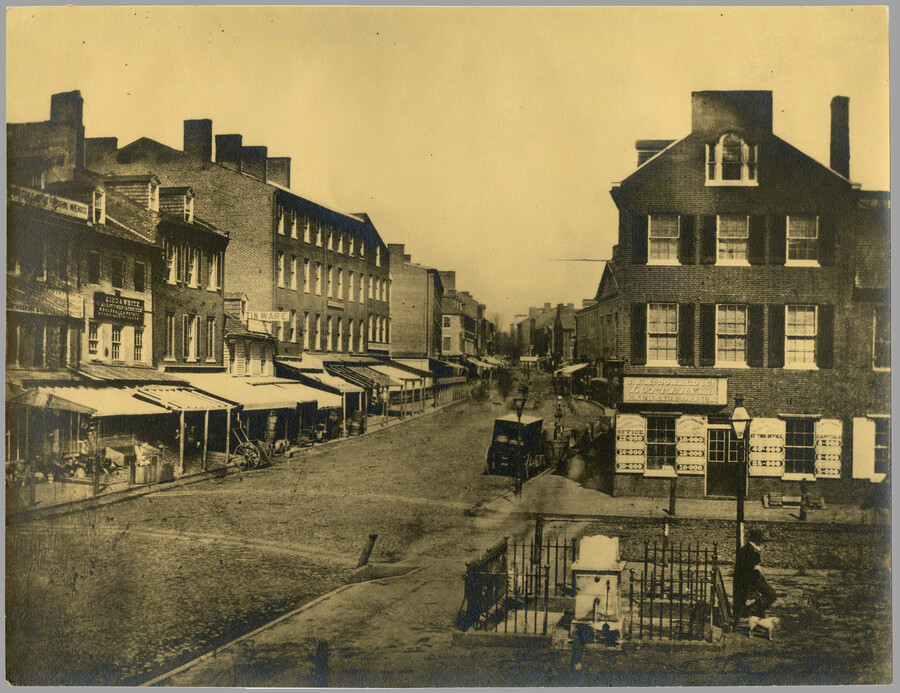

In 1800s Baltimore, immigration was booming. The population of Baltimore, around 27,000 in 1800, would increase over the century by 1800% to nearly 509,000 people.[4] In 1827 the Baltimore & Ohio Railway Company (B&O Railroad) began running railway operations from the piers of Baltimore to the interior of the United States. By 1852 these trains would transport goods and passengers from Baltimore City Harbor to New York, Washington, D.C., Chicago, St. Louis, and beyond, rivalling the Erie Canal in scope and leading to the creation of standardized time zones, above-ground telegraph poles (which would later become telephone poles), and the world’s first long distance railroad line.[5] Baltimore was second only to New York City in receiving immigrants to the New World, and the cultural melting pot was booming.

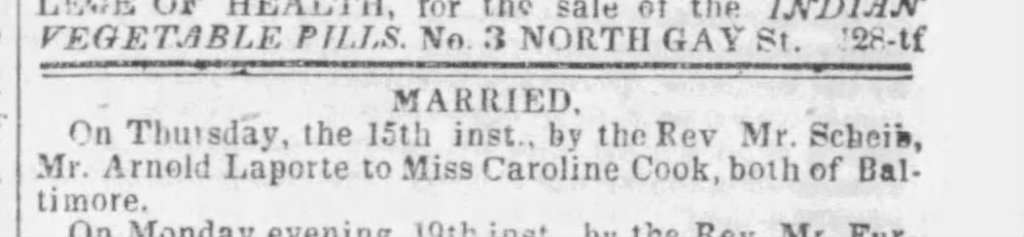

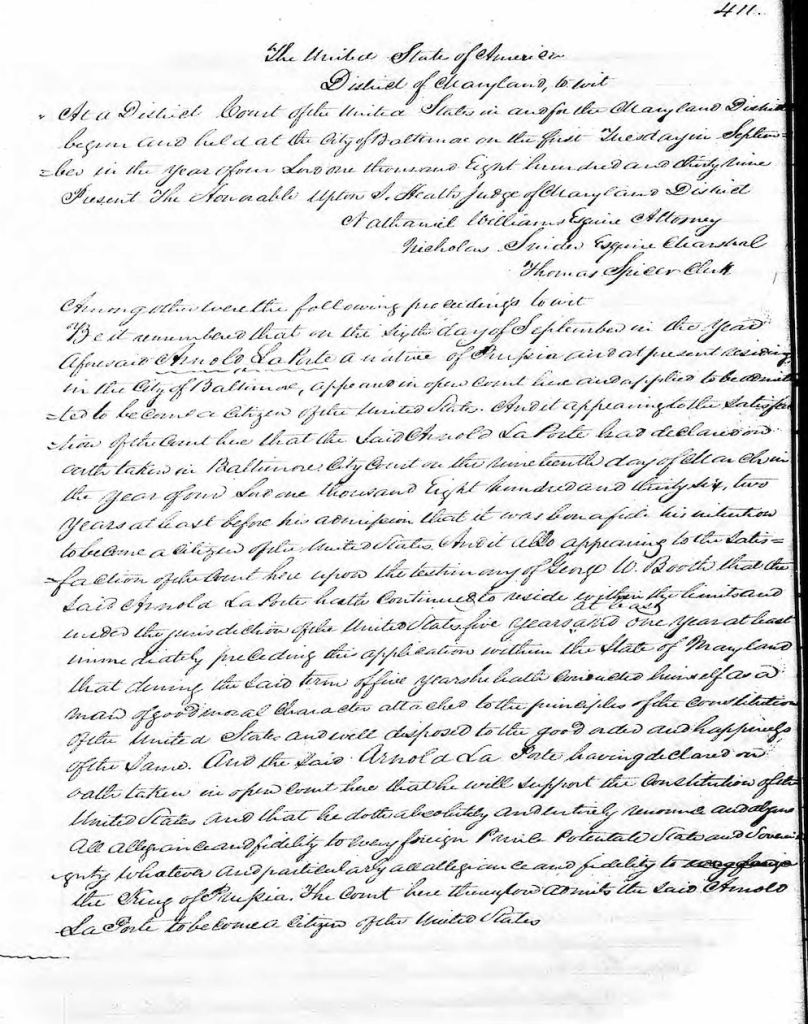

On November 15, 1838, Arnold married again, this time to Caroline COOK.[6] Arnold and Caroline settled in the 18th Ward of Baltimore City near what is now University Square Park. In September 1839, Arnold became a naturalized citizen of the United States.[7] The next year, around their second anniversary, Caroline and Arnold welcomed their first child, a son named William Henry. Within the next 20 years the couple would have 7 more children – Caroline Margaret (b. 1843), Charles Louis (b.1844), Clara Elizabeth (b.1848), Emma Lisetta (b.1849), Arnold Henry (b. 1853), Edward (b.1855) and Alice Loretta (b.1861).[8]

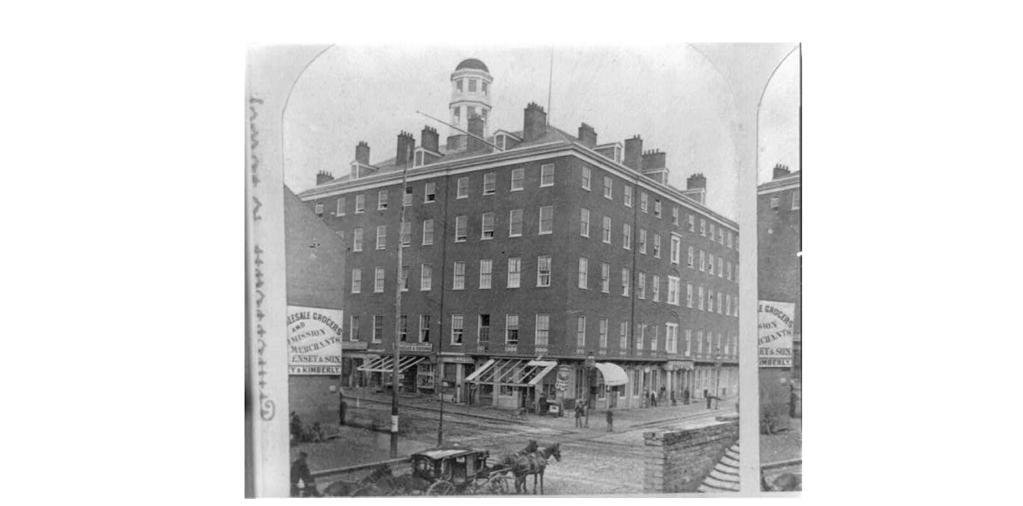

Arnold was a saddler – a harness maker – and considered himself a Frenchman. In Baltimore he set up a shop at 576 West Baltimore Street. He ran the shop successfully for 40 years. The family lived within one block of the shop for all 40 years as well, on Eutaw and Paca Streets. This part of the downtown area of Baltimore was historically known as home to an affluent German-Jewish community of the city.[9]

The LAPORTE family lived in Baltimore during a prosperous time for immigrants, yet it came with new struggles and uniquely American difficulties. In the time before the Civil War broke out, the state of Maryland, and especially Baltimore, played a nuanced and complicated role in the conflict. Maryland remained a slaveholding state, but it did not secede from the union during the war. Most of the population to the north and west of Baltimore were loyal unionists, while the farmers to the southern and eastern parts of the state leaned toward confederate sympathies.[10]

In the decade before the Civil War, street gangs operating as “political clubs” such as the Plug Uglies and Bloody Tubs made the city of Baltimore a dangerous place. These gangs were the brutal heavies of the Know Nothings. The Know Nothing Party was the party of power in Maryland, for the decade prior to the Civil War. It was progressive – pro women’s rights and civil rights – and nativist, and it was anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant. The party used the vicious gangs to block voting booths, violently attack opposition (in some cases, dunking their heads in vats of blood), and rig elections. Baltimore developed the nickname of “Mobtown,” full of thugs and immigrants – nearly a quarter of the population of the city was foreign-born.[11] By the end of the 1850s, the anti-Know Nothing candidates conceded defeat without question. At the end of the decade, three Plug Uglies were hanged for blatantly murdering two police officers in cold blood on the street. Their hangings and subsequent funerals drew thousands of Know Nothing supporters.[12]

On April 19, 1861, the first blood in the Civil War was shed in Baltimore when the 6th Massachusetts Infantry, switching trains downtown en route to Washington DC, were harassed and blocked from passing by pro-Confederate Baltimore citizens. The troops were attacked with rocks and bottles on Pratt Street. When the soldiers began to fire into the crowd in retaliation, a riot ensued between the citizens, the soldiers and the Baltimore police. The soldiers were finally able to reach the departing train, but they had abandoned much of their equipment and many men did not make it through. Five soldiers were killed and 36 were wounded. Over a dozen civilians also died. The office building of a German-language newspaper, known to be a Union supporter, was also destroyed during the riots.[13]

During the war, Arnold and Caroline and their children continued to live and work in downtown Baltimore. Their eldest sons, William and Charles, worked closely with their father. William was at varying times a harness maker for his father, a clerk, and a cigar maker. William also served in Maryland 2nd Cavalry Regiment for the Union during the Civil War.[14] Charles became a cigar maker and continued in that trade for the rest of his life.

Arnold and Caroline’s daughter, Emma Lisetta LAPORTE, married James J. W. TAYLOR on October 4, 1870 in Baltimore. Emma was 19 years old, James was 36. James was living with the LAPORTE family in the 1870 census as a boarder, and Emma was no doubt romanced by this older son of the Confederacy.[15]

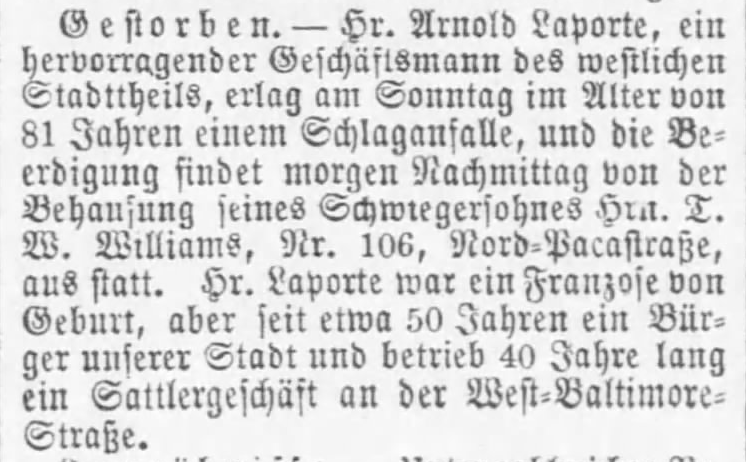

Arnold and Caroline remained in the same part of Baltimore for the rest of their lives.[16] In 1877, Caroline LAPORTE died at age 56. She was buried in the Baltimore Cemetery. William, the couple’s eldest son, died in 1881. After 1880, Arnold and his youngest son, Edward, a candy maker, moved in with his daughter Clara (now Clara WILLIAMS) and her family on North Paca Street.[17] Arnold died in Baltimore in the summer of 1885 of a stroke.[18] He is buried beside his wife.

Died. Mr. Arnold Laporte, an outstanding businessman of the western part of the city, died of a stroke on Sunday at the age of 81, and the funeral will take place tomorrow afternoon from the home of his son-in-law, Mr. T. W. Williams, No. 106 North Paca Street, from. Mr. Laporte was a Frenchman by birth, but a citizen of our city for about 50 years and ran a saddler store on West Baltimore Street for 40 years.

[1] https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Niedersachsen

[2] https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Westphalia_(Westfalen),_Prussia,_German_Empire_Genealogy

[3] Baltimore, Maryland. Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at Baltimore, 1820-1891. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration. Micropublication M255

[4] https://msa.maryland.gov/msa/mdmanual/01glance/chron/html/chron.html

[5] The History of Baltimore, The City of Baltimore Comprehensive Master Plan – page 25.

[6] The Baltimore Sun – 22 Nov 1838 – Page 2

[7] National Archives and Records Administration (Nara); Washington, D.C.; Naturalization Records; NAI Number: 654310; Record Group Title: Petitions For Naturalization, 1903-1972; Record Group Number: Rg 21

[8] U.S. Federal Census Year: 1870; Census Place: Baltimore Ward 14, Baltimore, Maryland; Roll: M593; Page: 164; Dwelling: 989

[9]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eutaw_Street#:~:text=Eutaw%20Place%20was%20called%20Gibson,are%20located%20along%20Eutaw%20Street.

[10] https://www.visitmaryland.org/article/civil-war-history#:~:text=Although%20it%20was%20a%20slaveholding,were%20sympathetic%20to%20the%20Confederacy.

[11] https://www.baltimoremagazine.com/section/historypolitics/city-of-immigrants-the-people-who-built-baltimore/; https://www.executedtoday.com/2015/04/08/1859-baltimores-plug-uglies/

[12] https://www.executedtoday.com/2015/04/08/1859-baltimores-plug-uglies/

[13] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baltimore_riot_of_1861

[14] National Park Service, Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System, online http://www.itd.nps.gov/cwss/

[15] U.S. Federal Census Year: 1900; Census Place: Abingdon, Harford, Maryland; Roll: T623_623; Page: 13A; Enumeration District: 141.

[16] Boyd´s Business Directory of the State of Maryland, 1875, Page 274

[17] U.S. Federal Census Year: 1880; Census Place: Baltimore, Baltimore (Independent City), Maryland; Roll: 505; Page: 346B; Enumeration District: 206

[18] Newspapers.com – Der Deutsche Correspondent – 1885-09-01